By John Thompson, Chief Creative Officer, TrueSense Marketing

By John Thompson, Chief Creative Officer, TrueSense Marketing

Consumer marketers, corporate B2B marketers, and fundraisers all use some combination of emotional and rational drivers in the persuasive stories they tell. And the reason why is the same: to motivate their audiences to take action. However, the difference is in the “how.” Marketers rely more on rational arguments (price, competition, gratification, ROI, etc.) in their attempts to motivate donors. However, fundraisers lean more on core human emotions (compassion, outrage, sympathy, empathy, and the noble senses of justice, fairness, rights, etc.).

Triggering these emotional drivers often spells the difference between success and failure, which are measurable with very real revenue, volunteer and activist metrics, and outcomes.

There is risk with leaning heavily into emotion because it can be perceived so subjectively. Furthermore, it is important to stay current with trends in society. For example, today’s sensitivities focus around the use of equitable, dignified, and appropriately diverse images and stories in the fundraising messages delivered to donors.

But ethical storytelling goes far beyond diverse creative content. An even deeper and more profound issue may revolve around positioning — specifically the way donors, organizations, and their clients are positioned relative to each other.

Why is this important? Because we live in fraught times. We are reminded every day of the polarity in our society. Increasingly, much social discourse evokes an Us vs. Them mentality, which is only compounded by the very real economic, racial, cultural, social, and political inequities that divide us.

The Stories We Told

Sadly, for many years, fundraisers played a part in this polarity. They were convinced that hyperbole was justified, as long as it opened the revenue sluice gates for their missions. The worse the problem sounded and appeared, the greater the motivation to give.

Often the stories told were built on the basic premise that great evils like hunger, war, disaster, poverty, and disease happened to others.

- In some cases, compassion was triggered by a sense of principled obligation: “It’s the [religious, moral, American, etc.] thing to do.”

- In other cases, compassion was triggered by fear: “But for the grace of God this could happen to me and my family.”

Donors were positioned as saviors and heroes for Them, who were positioned as victims of that great evil, defined by their deficits, and bereft of any agency for repairing their own lives. In so many fundraising stories, a bright spotlight shone on the gap between Us and Them — and by doing so, contributed to society’s larger systemic inequities.

Thankfully, a great deal of thoughtful, provocative, and healthy conversation has taken place over the last several years about the unintended consequences of “saviorism.”

On one hand, this conversation has made us rethink — as marketers and fundraisers specifically — the dangers of this sort of messaging in our society today. On the other, it offers opportunity to use the fundraising industry’s unique communication role to influence the way our society begins to view philanthropy. Not through an Us vs. Them lens, but through the more ethical lens of We.

It is hard. It is sometimes uncomfortable. But it is necessary.

5 Tips Toward More Ethical Fundraising Stories

1) Identify Community as the Fourth Philanthropic Stakeholder

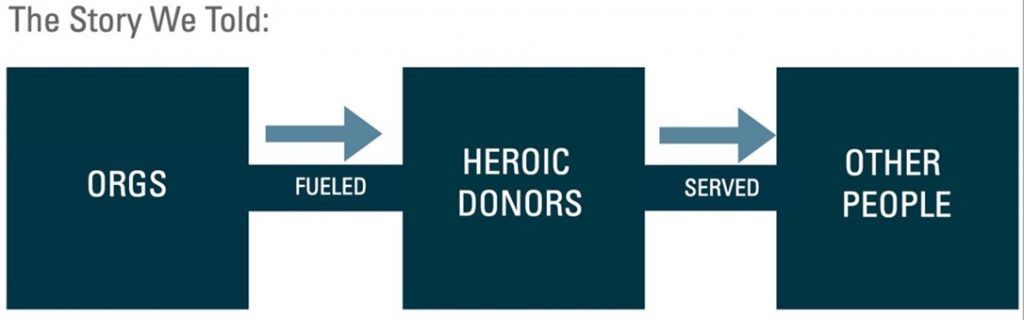

The “Donor Hero” construct suggested a three-stakeholder, linear relationship:

The notion here is that the Organization endows the Donor with heroic qualities to solve the issues facing the Client.

Aside from reinforcing saviorism, this relationship ignores an important beneficiary of philanthropy: the Community. In short, what benefits one of us in the community benefits all of us, because the community itself becomes a better place in which to live. (And community could be a neighborhood, city, country, ecosystem, or even the world.)

The high tide that floats all boats. And so, a new construct:

One that sets the philanthropic story into the larger context of community and equalizes all three traditional stakeholders as beneficiaries — with the ultimate beneficiary being the community in which all can thrive. Moreover, the process is never linear. It is continually circular, based on equitable, ongoing partnership among all stakeholders.

2) Define Clients by Their Strengths, Not Their Deficits

Recognize that those who benefit by moments of charity, as members of the larger community, deserve the same dignity, equity, and agency as all other members of the community. And so:

- Describe neighbors facing hunger, NOT hungry people.

- Describe kids in under-resourced neighborhoods, NOT at-risk kids.

- Describe Dave as a father and husband facing cancer, NOT a cancer patient.

Like everyone, including donors, they experience challenges in life from time to time, and their specific story at this moment in time does not define them.

3) Use Strength-Based Messaging to Tell Your Stories

According to Feeding America, in guidelines provided to its network of food organizations,

“Strength-based messaging emphasizes the strengths, opportunities, and power of an individual, group, or community. It represents people positively, in a way that feels true and empowering to them.” They go on to identify 5 characteristics of strength-based messaging:

- Leverages person-first language that focuses on the individual, not their circumstances.

- Focuses on a person’s contributions and aspirations, not the challenges they face.

- Recognizes we all face obstacles and require support.

- Emphasizes the collective benefit of addressing the root causes of inequity.

- Considers lived experience and amplifies community voice.

4) Use a Simple Self-Test

The creative team at M+R suggests this simple self-test to determine the ethical qualities of fundraising creative. Ask yourself:

- Are there considerations around diversity and inclusion (including issues of race, language, class, ability, or gender of the speaker, audience, or subject) that we should think about as we create our messages?

- If the subject of this creative were to see it, how would they feel?

- Is this creative an opportunity to advance our core principles?

5) Seek Balance

Fundraisers must approach ethical storytelling with a degree of clear-eyed pragmatism. Responsible fundraising creative cannot ignore its core raison d’être: to raise the funds that enable the mission.

There are 4 truths that will never change in the fundraising industry:

- First, bad things will always happen in this world.

- Second, donors will always be the primary target audience for fundraisers.

- Third, donors will always be human and, therefore, be susceptible to emotional triggers.

- Fourth, fundraising creative will also always be built on a core creative equation that states Resonation (emotional triggers) plus Demonstration (rational arguments that support the efficacy of the nonprofit’s mission) equals Motivation (the decision to donate).

Given these truths, the trick will be finding the appropriate balance between organizational values, societal ethics, and financial responsibility. And that fulcrum will probably move as mission, audience, offer, and programs change, even within the same organization.

Sympathy or Empathy? A New Potential Driver

In recent primary research TrueSense Marketing conducted on Salvation Army COVID-19 donors, findings indicate that those who made gifts during the COVID-19 pandemic were much more likely to continue to do so if they themselves were directly impacted by the disease.

As an example, older donors were more motivated to give by stories of isolation and immobility if they experienced it themselves. Likewise, younger donors were motivated by stories of economic hardship and family food insecurity having lived through similar anxieties.

In short, the emotional driver for many of these COVID-19 donors was empathy, not sympathy.

This suggests a new creative approach — one that supports the new, strengths-based, community-forward messaging outlined above:

Storytelling that seeks not a sympathetic response, but an empathetic one. A donor — and challenge — positioned in such a way that a neighbor’s (or animal’s, or ecosystem’s) experience is not something to be considered from a distance, but one that a donor could easily find parallels to and benefits in their own life and community.

Imagine the effect a consistently applied movement toward empathy could have over time, across a donor audience, across a community, across society.

Not another demonstration of Us vs. Them, but a new paradigm built on the concept of We. Fundraisers, and the stories they tell, are uniquely positioned to effect positive change in their donor audiences — and perhaps, someday, in society at large.

It all starts with an ethically sound, responsibly positioned, and (still) motivating story.