By Jessica Browning, Principal and Executive Vice President, Winkler Group

By Jessica Browning, Principal and Executive Vice President, Winkler Group

For too long, we’ve been mesmerized by the one-stop-shopping lure of the megadonor and the power of the major donor. Who hasn’t been tempted by the idea of meeting a fundraising goal with fewer asks?

This obsession—fueled by reduced tax incentives for giving, societal shifts, and nontraditional forms of giving—has put us in a precarious position. Because we’ve ignored the everyday donor, they’ve stopped giving and now our traditional philanthropic ecosystem is out of whack.

Let’s take a look at how we got here, why the alarm bells are ringing, and how we can fix the problem.

Economic and Societal Shifts

“The Shifting Landscape of American Generosity,” published by the Generosity Commission earlier this year, identified the reasons we’re seeing fewer monetary donors.[1]

- Economic precarity and the lasting impacts of the Great Recession

- The decline in Americans’ religious affiliation and participation

- A declining trust in nonprofits and institutions in general

- Social disconnection or what Surgeon General Vivek Murthy describes as an “epidemic of loneliness and isolation”[2]

If we stay on this path, we will continue to see declines in the number of Americans who give to 501(c)(3)s. More giving will shift away from nonprofits and toward crowdfunding and person-to-person giving. We’ll be less prepared for the impacts of an economic downturn. Worse yet, we’ll set ourselves up for future failure when we don’t cultivate our pool of younger, emerging donors.

We’ll also see an imbalance among sectors. Because the wealthiest donors tend to support arts organizations, higher education, and health-related causes, other sectors like human service organizations and religious institutions will be more vulnerable.

Fewer Volunteers

A reason for the decline in everyday donors is the shrinking number of volunteers. AmeriCorps data shows the volunteer rate fell from 30 percent in 2019 to just 23 percent in 2021—continuing the decline that began in the mid-2000s.[3]

The decline may be blamed on the same factors influencing donor decline. It could also be us because we make it too hard to volunteer. With limited spots and lots of hoops to jump through, we put up a lot of barriers to volunteering.

Take my mother, for example. For years, she has volunteered to read to children who are falling behind. After Covid, she wanted to volunteer closer to home and chose an early childhood center where she is a long-time donor and past board member. The organization’s background check policy included fingerprinting. The skin on my 82-year-old mother’s fingers is so worn that it’s impossible to find fingerprints. They couldn’t make an exception. Now she feels unwanted by the organization she’s long championed.

Yes, managing volunteers can be time-consuming and frustrating, and security measures like background checks are important. But connecting someone—a prospective loyal donor—with your mission is worth it. “When you volunteer your time, you see the need and you’re more compelled to donate,” explains my mom.

2017 Trump-Era Tax Reform

Recent tax reform has eroded giving from everyday donors. For 93% of Americans, a tax deduction for charitable gifts is no longer a realistic choice.

We used to gather giving statements or receipts for the bags of clothes we dropped off at the thrift store because we could deduct those contributions from our taxable income. It wasn’t the reason for giving, but for many of us, it was a worthwhile incentive and motivation to give more.

The Tax Cut and Jobs Act (TCJA) that passed in late 2017 raised the standard deduction and eliminated the option for most Americans to itemize their deductions, including their gifts to charity.

According to the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center, the percentage of American households donating to charity fell from 66.2 percent in 2000 to 49.6 percent in 2018, the first full year the TCJA was in effect.[4] Today, only 7.5% of Americans itemize their deductions, meaning the financial incentive to give is concentrated among a sliver of Americans.

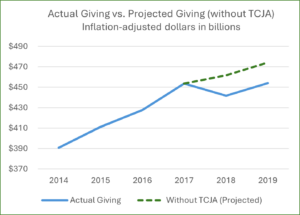

“Tax Incentives for Charitable Giving: New Findings from the TCJA,” a working paper drafted by Xiao Han, Daniel M. Hungerman, and Mark Ottoni-Wilhelm and published by the National Bureau of Economic Research, finds that charitable giving has fallen by nearly $20 billion annually as a result of the TCJA.[5]

“Tax Incentives for Charitable Giving: New Findings from the TCJA,” a working paper drafted by Xiao Han, Daniel M. Hungerman, and Mark Ottoni-Wilhelm and published by the National Bureau of Economic Research, finds that charitable giving has fallen by nearly $20 billion annually as a result of the TCJA.[5]

This chart illustrates the gap between actual charitable giving and the projected trajectory had TCJA not been passed.

The TCJA has also fueled our hyper-focus on giving from the wealthiest Americans because it increased the limit on deductions for charitable contributions from 50 percent to 60 percent of adjusted gross income (AGI). For example, a donor whose AGI is $1 million a year can now deduct up to $600,000 in charitable gifts rather than the $500,000 they could deduct before the TCJA.

Us (Fundraisers)

Perhaps the biggest hurdle is that everyday donors don’t think we appreciate them.

Case in point: a friend of mine has volunteered with the same organization every month for the past three years. Yet, when they send newsletters and appeals to her house, they send them only to her husband. And they misspell his name!

“Why would I trust them with even more of my money?” she says with an awkward laugh.

We’ve all heard horror stories like this. Ironically, as we amass more tools like AI and predictive wealth screening—tools that supposedly make it easier for us to communicate more authentically—we hear these cases about donors being alienated even more.

The Case for the Everyday Donor

The pandemic era proved that it’s worthwhile to engage and steward the everyday donor. The CARES Act of 2021 temporarily enabled all taxpayers (including non-itemizers) to claim a modest deduction for charitable contributions. The result: $18 billion in new gifts from 47 million households. And nearly a quarter of the households (21.3%) had adjusted gross incomes below $30,000.[6]

Once we acquire everyday donors, it’s just as important that they feel valued. Here are some strategies to find and keep supporters:

- Use your CRM’s AI-enabled powers to segment by donor personas and then share stories tailored to their interests. For example, a hospital system can share the heartwarming story of a child who beat cancer with donors to their children’s hospital—and news of groundbreaking cardiovascular research to their heart center donors.

- Use a platform like Gratavid to show your donors their impact first-hand. Imagine how donors to a clean water charity, for example, would react to seeing children in a remote African village taste flowing fresh water for the first time. Combine the video with the message, “you made this happen,” and you have a powerful case for support.

- Give donors the exclusive by sharing behind-the-scenes information on research and new programs. Survey donors on strategic issues and then communicate the results.

- Advocate for the Charitable Act: Use AFP’s form (link to https://afpglobal.org/policy-advocacy/charitable-act) to send a pre-written email to your senators and representative and encourage them to permanently enact a charitable deduction for non-itemizers.

Why Diversify?

Just like a strong stock portfolio, our donor pool must be diversified. By ignoring our everyday donors in favor of larger ones, we all lose. We end up with top-heavy organizations that are vulnerable to the unexpected. Instead, strive for the pyramid on the right—the one with the broadest base of support.

As fundraisers, there are challenges we won’t be able to overcome on our way to building a diversified donor portfolio. Social isolation, economic fluctuations, and declining religiosity are beyond our control.

But it is within our power to make the case for philanthropy and demonstrate its impact to those who fuel our missions.

About the Author:

Jessica Browning, principal and executive vice president of the Winkler Group, has more than 30 years of nonprofit experience. Her specialty is donor communications. She holds a B.A. from Duke University and an M.A. and M.B.A. from the College of William and Mary.

[1] While some will argue that generosity is more than the financial, this paper focuses on contributed revenue.

[2] “The Shifting Landscape of American Generosity,” The Generosity Commission, June 2024, https://www.thegenerositycommission.org/generosity-commission-report/

[3] “The Shifting Landscape of American Generosity,” The Generosity Commission, June 2024, https://www.thegenerositycommission.org/generosity-commission-report/

[4] https://taxpolicycenter.org/briefing-book/how-did-tcja-affect-incentives-charitable-giving

[5] https://www.nber.org/papers/w32737?utm_campaign=ntwh&utm_medium=email&utm_source=ntwg6

[6] https://www.ncsl.org/state-legislatures-news/details/spreading-cheer-through-charitable-giving#:~:text=The%20temporary%20incentives%20boosted%20giving,4%25%20from%20the%20previous%20year.